By Bob Hayes - Managing Director of the Security Executive Council, Kathleen Kotwica - EVP and Chief Knowledge Strategist for the Security Executive Council, and Marleah Blades - Projects Editor for the Security Executive Council

What is the definition of corporate security? Until as recently as 20 years ago, corporate security centered squarely on the programs Security owned – the ones for which the security function was directly responsible and accountable in terms of operations and budget. Access control and badging, guard services, personnel protection, and travel security generally fell under this umbrella.

Lawsuits, investigations, and special projects would bring Corporate Security out of the bunker to work directly with HR, Legal, Compliance, or Audit, but ongoing collaborative partnerships with other functions were less common. That’s not to say that nurturing communication and engagement with functions outside of security hasn’t long been a best practice; we at the SEC have evangelized this since our inception, as have many other thought leaders. But in reality, collaboration tended to happen primarily on an ad hoc basis.

Now, years of profound advances in computing, networking, mobile technology, data management, and machine learning have transformed how organizations work. Businesses today operate within a much more complex, sophisticated, and interconnected competitive universe than they did 20 or even 10 years ago. One of the impacts of these transformations on Corporate Security is that cross-functional partnerships, once considered a “nice to have,” have become a risk management imperative.

Senior Leaders Expect Security to Team Up

Time and again, our subject matter experts have reported that in the C-Suite, there is an expectation that all business functions engage actively with their stakeholders across the organization to build understanding, share information, and optimize processes. Corporate security is not exempt from that expectation.

In 2021 and 2022, the Security Executive Council’s Security Leadership Research Institute (SLRI) worked with Kennesaw State University’s Coles College of Business to examine the structures of collaboration specifically between corporate (physical) security and information security functions and the factors that build strong collaboration in any framework. One participant in the study shared the following thought about the power and influence of reliable collaboration:

“I think it brings what I would call a calming effect on the business that they realize that regardless of what vector, if there is a security threat to the company, we’re going to be dealing with it the best way that we possibly can, bringing the best minds to the table and hashing it out, regardless of what titles are out there. VP, CIO, CSO, Head of Security – it doesn’t really matter.”

Success in our complex, global business environment requires organizations not only to nimbly manage security threats but to take smart risks – to expand into new territories, invest in innovations, and develop new partnerships. The corporate security function can play a critical role in enabling smart risk-taking by providing risk intelligence and assuring the safety and security of the organization’s physical assets, people, and operations in every venture – not just in the few programs they “own.”

Newer Technologies Bring Functions Together

Some of the same technology advances that have driven overall business change have transformed security-relevant applications, enabling the operational expansion of SOCs and GSOCs, further use of data intelligence and analysis for global threat identification and risk management, end-to-end supply chain security, and enhanced critical event response, to name a few.

All these tools better enable Corporate Security to manage risks in our era of polycrisis. Expanded initiatives like these also necessitate the continued input of multiple stakeholders outside of security. Imagine initiating a GSOC without first discussing its requirements with IT or the business functions from whom the data will need to be collected. Imagine implementing comprehensive supply chain protection without asking regional site managers about their needs, operations, and risks.

But to engage cross-functional partners and incorporate their input effectively, corporate security leaders and staff must learn skill sets that may differ from those they expected to need in the security field.

Broader Skill Sets Required

In 2007, the SEC developed a model of the skill sets that would help Security succeed in a changing business and risk landscape. The project began with a deep dive into the backgrounds from which security leaders were hired. At the time, the security industry was experiencing a shift from hiring primarily out of military and law enforcement backgrounds to hiring more frequently out of business backgrounds, with information security experience quickly gaining. This led to an examination of the valuable skills that come out of experience in each of these different fields, and a recognition that a blended skill set would be a boon for security career options in the future.

Earlier this year, we released a revised version of this Next Generation Security Leader model that reflects our post-COVID global reality.

Click here for a larger representation of this graphic.

Click here for a larger representation of this graphic.

While some of the skill categories and many of the individual skill recommendations have changed, the overall message remains the same: Security leaders who pursue a blended skill set including elements of executive leadership, business acumen, emerging issue awareness, cybersecurity and information security, skills specific to security technology and concepts, and knowledge of deterrence and enforcement will have the best opportunities to excel in a continually changing landscape.

Leaders with diverse skills will also be more capable of communicating effectively in business terms, understanding the operations and concerns of business function leaders, and building the influence required to lead cross-functional teams. They may also be more highly valued and compensated by the organization. And where a single leader cannot incorporate all the skills in the list, a security team made up of individuals with knowledge or experience in the different categories will be more able to rise to a variety of risk management and business challenges.

Evaluate the Security Role Differently

With today’s expanded capabilities, Corporate Security’s scope and structure have branched out in many organizations. In others, however, evolution has occurred more slowly. This variance has always been with us – the answer to “What is Corporate Security?” has always been, to some extent, “It depends.”

It depends on the circumstances, conditions, corporate culture, and resources (C4R). It depends on industry and sector, on executive engagement, on Security’s functional and leadership maturity.

The SEC uses a fairly simple visual to assist security leaders in defining and communicating to executives what corporate security is in their own organizations by identifying their realms of responsibility, levels of collaboration, and their potential for growth into other areas.

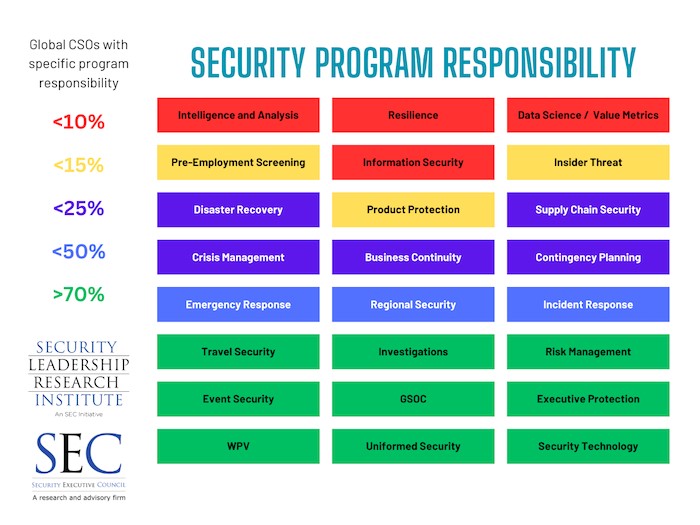

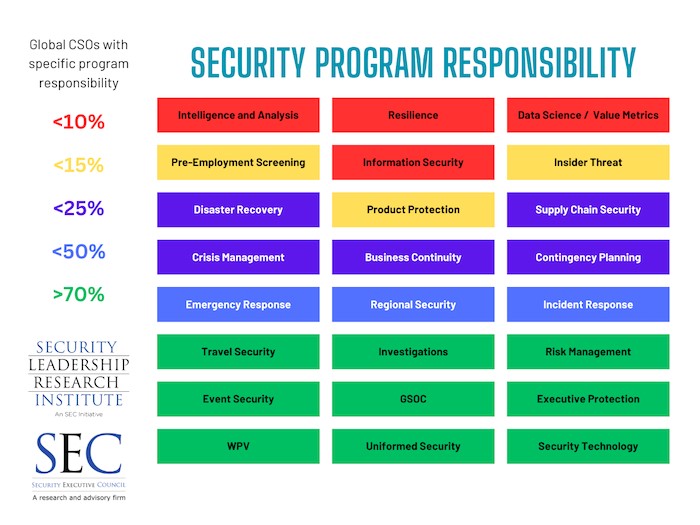

This chart is based on SLRI Research on more than 400 corporate security leaders’ self-reported program structures and responsibilities. Analysis found that more than 70% of respondents had responsibility for the six programs in green. Less than 50% had responsibilities that expanded to the three programs in blue, less than 25% had responsibility over the purple programs, and less than 10% reported that they were responsible for the four programs in red.

We provide security leaders with a colorless version of this graphic and ask them to identify programs they own, programs they partner on, those they consult on, those they’re uninvolved in, and those that don’t exist at their organization. Then we look more closely at the partnered programs, identifying which functions they partner with and estimating the percentage of responsibility of each party. This process not only provides clarity to all parties, it helps reduce redundancies and achieve stronger accountability, and it helps identify possibilities that haven’t yet been explored.

The majority of corporate security functions own between five and 10 of the programs in the graphic, with varying degrees of participation in the others.

While security success in years past may have looked like a lot of programs marked “Own,” “Partner” and “Consult” may be the way of the future.

Leading without Owning

Today, Corporate Security isn’t likely to own all programs that manage risk. But the corporate security function has the opportunity to act as the trusted advisor on risk to both risk owners and stakeholders, providing a shared service that reaches across the enterprise.

Building the credibility and influence to become that trusted advisor may take time. Here are some helpful areas to focus on, based on SEC research and collective knowledge.

Build trust. The SLRI/Kennesaw State study on physical and cyber/information security collaborative structures identified a theme of trust building as a crucial component to effective partnership. “Trust between the two orgs is critical;” said one participant. “We have to think about one another and not throw one another under the bus.”

“Trust is critically important because it helps execs trust that you’re bringing unbiased objective analysis and good judgment,” said another. “Hire for collaboration in your teams. Be willing to speak frankly and negotiate.”

Use meaningful metrics. Meet with cross-functional partners to find out what they value within their functions, and develop security metrics that show how Corporate Security’s services contribute to those outcomes. Strong, reliable data can transcend barriers of language and distrust if analyzed and communicated well.

Document expectations and strategies. It’s important that commitments and expectations in cross-functional initiatives are documented and approved by all parties. This provides transferrable clarity, strategic support, and accountability. We at the SEC have used the Concept of Operations process to help achieve this, with much success.

Communicate the Possibilities

As the diversity of security's role has grown, it’s become more difficult for business functions, executive management, and sometimes even security leaders themselves to ascertain the scope and depth of what Corporate Security does or could do. Corporate Security teams have skills and knowledge that are widely beneficial across the organization, but if senior management doesn’t recognize that potential, it cannot be fully realized.

We have seen executive teams have “a-ha” moments when presented with the visual of the Security Program Responsibility chart showing the extent of Corporate Security’s cross-functional involvement, because they simply had no idea how far the function’s reach extended. Once they see it, it’s important for the security leader or an advisor to follow up by explaining the details of Corporate Security’s capabilities within each program area.

We can’t overstate the importance of clearly communicating security’s diverse roles and value to executives. It will build influence within the organization and will also cement the security leader’s identity as a team player, someone reaching out across functional lines to offer services that improve the risk posture of the company. If there is any question about whether the C-suite understands Security’s role and capabilities, now is the time to educate them.

Next Steps

The Security Executive Council has over 20 years of proven success at assisting Security Leaders communicate to executives about what corporate security is and identifying ways to build influence within the organization.

Contact us to discuss your situation and find out how we can assist you.

Download a PDF of this page below: